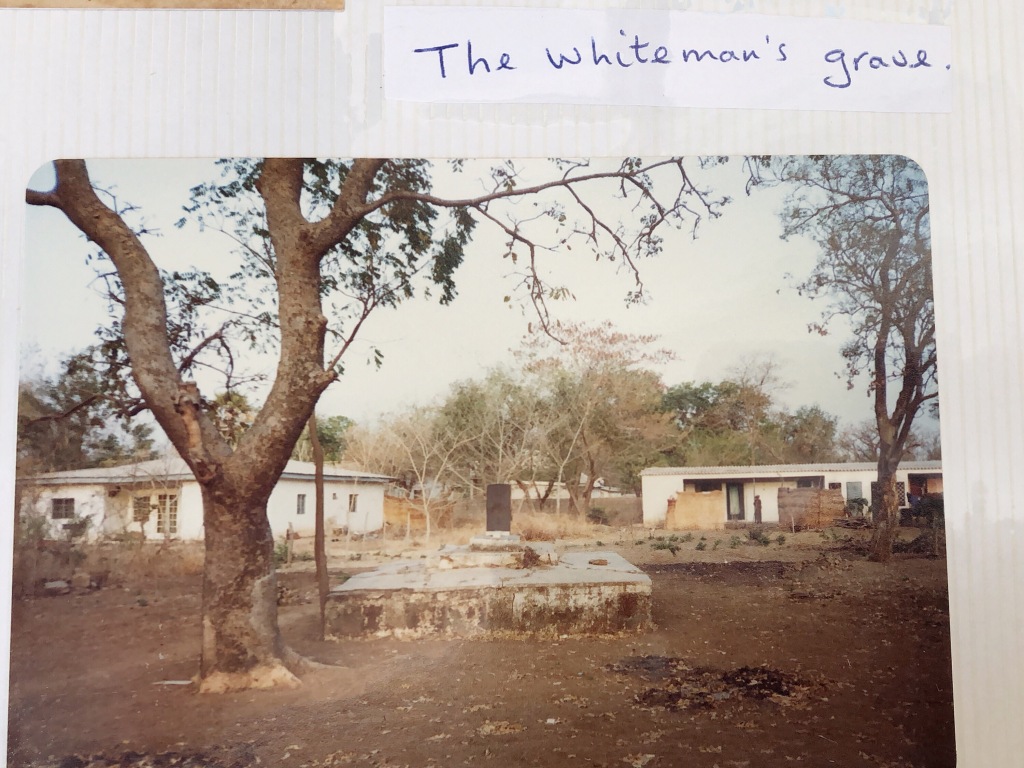

Various Homes: The White Man’s Grave

‘Home’ for Christmas 1980 was the ‘White Man’s Grave’. Richy (10), Mikey (8), Andy (4), and I were there only for a few weeks during the school holiday, but it was such an unusual place that I had to include it in my list of homes. Husband Paddy had recently moved to northern Nigeria, to start up a World Bank agricultural project. He was the only staff member there, so it was the five of us for Christmas in a bungalow on the outskirts of Bauchi, a traditional Nigerian Muslim town.

The house had no memorable features, except the bathroom. This was too small to accommodate even an ordinary-sized bath, so a hole had been cut into the wall allowing part of the bath – the end without the taps – to jut into a bedroom. A novel solution, you must admit. (Paddy told us that one night he had slept in the bath to escape vicious army ants that marched through the house.)

The surroundings of the building were bleak and desolate in the dry harmattan season, but, again, there was one striking feature. A cement slab, larger than a table-tennis table and raised to chair-seat-height, dominated the bare and dusty ground. On its cracked and weed-strewn surface was a smaller slab of grey cement, with a large white cross, fashioned from bricks. Below the cross etched into the cement in capital letters, were the words:

IN FONDEST MEMORY

OF MY DEARLY LOVED HUSBAND

MAJOR J. E N. PRICE.

BORN 1874

PASSED OVER 1918

An austere Portland stone War Graves Commission headstone, which must have been added later, looked out of place on the dilapidated grave.

As we had no garden chairs, we sat each evening for sundowners along the edge of the White Man’s Grave – Paddy and I with cold beers and the boys with the treat of a Coke or Sprite. We raised our glasses and drank a toast to the unknown white man and speculated as to why he had been there and how he had died so far from his homeland. Was it the war that killed him? Unlikely as although Nigerian regiments took part in the war, there was no fighting within the country. Perhaps he caught the Spanish ‘flu as it swept through Africa, or maybe it was malaria or dysentery, the fate of so many. Did his wife learn of her husband’s death through a formal army notification? Did Major Price leave children ‘at home’ to grow up without a father? There was no way to answer these questions.

We also knew little of the Tuareg men who arrived at the house each evening. Known as the ‘Blue People’ because the indigo dye of their clothes stains both their skin and nails, they were dressed in flowing blue robes and blue-black turbans that left only deep-set steely eyes and dye-stained hands uncovered. As the sunset, the two figures emerged through the haze of the dwindling dust-laden light. With their tall upright stature, and curved leather-sheathed daggers slung from their shoulders, the men were a formidable sight. Arms raised high in greeting was our only communication as we had no language to converse with these Berber-speaking men. With the first chink of morning light, they were gone.

In days gone by, these desert people would have driven caravans of camels across the Sahara – trading in gold, spices, salt and slaves. Or they might have been warriors, raiding those same caravans or stealing from settlers living along the desert’s edge. Their families would have been nomadic pastoralists, moving with their goats, sheep and camels and sustained by the milk, meat and hide of these same animals. Changing times made it difficult for the Tuaregs to continue their traditional way of life. Forced south from their Sahara homelands in Mali or Niger, they needed to earn money to feed their families and send their sons to school. I don’t believe that we required protection, as northern Nigeria was then a safe and peaceful place, but being a nightguard was an appropriate job for these proud, warlike people.

***

From out of our suitcases came all that was needed to prepare for the Christmas festivities. The boys made paper-chains and hung them from the ceiling. We found a thorn tree branch and transformed it into a Christmas tree, tying a spangled fairy on the topmost twig. We snuck off to various rooms to wrap parcels in secret, before piling them around the tree. I covered the cake with marzipan (rolled out with a beer bottle) and covered this with a thick layer of snowy white icing. While the children disappeared outside to scrape the last of the icing out of the bowl with grubby fingers, I placed a tiny Santa in his reindeer sleigh on top of the cake. All was ready, and it was Christmas Eve.

Below his khaki shorts, Paddy wore knee-high socks. These made ideal stockings for Santa to fill. We left a window open as there wasn’t a chimney. No one queried how Santa would travel to this distant place or how he would squeeze his portly body through the burglar bars. We left him a welcoming mince pie and a tot of whisky to refresh him after his long dusty journey. As each of the children placed a stocking across the bottom of his bed, I was reminded of Christmas when I was young. Christmas stockings for me and my two younger brothers had been our father’s long socks. I remembered waking early on Christmas morning and stretching out my feet to feel for the weight of the full stocking, and the fun of pulling out one by one the goodies stuffed into that distorted leg. On that Christmas morning in Bauchi, long before Paddy and I were awake, the boys had emptied their stockings and found the assortment of nuts, fruit, sweets, games and books that Santa had brought. Four-year-old Andy could not contain his excitement for long.

“Mummy, look, Father Christmas did come. He brought me a Garfield comic book.”

“Strange that Father Christmas knows that Andy loves anything to do with cats,” said Mikey provocatively.

“Yes, it’s amazing what he knows.” I agreed. “Come here Andy, I’ve got something to show you.” He followed me outside where I pointed to the ground. “Look there are the marks of a camel’s feet in the sand. Father Christmas must have come by camel.”

“Oh, Mum, that’s amazing. I must show my brothers.” He ran inside and dragged Richy and Mikey away from their Beano comic books. They feigned incredulity, but I sensed their disbelief.

Later Richy cornered me. “Mum, what are those marks in the sand?”

“They look like camel footprints.”

“Mum ……” Boarding school had placed doubts about Santa and the Tooth Fairy, although the gifts they brought were still acceptable.

I refused to say any more. Even if the magic of Santa was almost gone, I was not going to be the one to dim it completely.

I did wonder what made those imprints in the sand. The Tuareg guards had small charcoal braziers to brew tea and warm their hands as they sat outside through the long cold harmattan night. The base of the braziers left marks in the sand. Perhaps these were the footprints of Santa’s camel.

Recent Comments